Free-form Friday

The hardest thing about writing is being sure that your reader will get something from the marks on the page similar to what you had in mind when you made them.

I have a bit of a problem as a musician. You see, people listening to me play don't hear the music I think I'm playing. And if I listen to a recording of my performance, it isn't nearly as good as what I thought I played. This is generally not a problem since I never try to accompany anyone else.

But a writer faces a similar but more daunting challenge. Unlike playing music for someone where you can get some idea from their expression as to whether they're enjoying the music or not, a writer must encode ideas and mental images as words on a page in a medium that can be consumed at another time and place. There's little opportunity to respond to feedback once the words have been printed and distributed. Much of the art and craft of writing comes down to learning the techniques and conventions that have been generally successful at conveying ideas to readers.

Put more simply, figuring out what I want to say is often easier than figuring out how to say it so that you'll come away thinking about roughly the same thing I had in mind.

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Many people use. Some people make.

This is a place to talk about that road less traveled.

Friday, April 30, 2010

Thursday, April 29, 2010

The Voice of a Book

Reading thuRsday

[I wrote the following in March, 2009]

I've been thinking about voice as I've caught up on my Newbery reading. I was particularly struck by the voices in Niel Gaiman's The Graveyard Book and in Savvy by Ingrid Law.

Savvy is the kind of 1st person narrative that comes first to mind when we talk about voice. The 13-year-old narrator sounds like a unique individual from the beginning.

The Graveyard Book is 3rd person (with occasional narrative intrusions), but it has voice too. How so? I don't have specific examples, but it's easy to imagine that the story would have been much less charming if told differently.

The notion that voice = characters-with-attitude is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg (if it doesn't miss the point entirely). I think voice = storytelling.

Go back to the primordial camp fires. What has always set the storyteller apart from the rest? The way they tell the story. In the old days, every one knew the story but some could tell it better than others.

This gets to the heart of voice--your voice as an author: it's about how you tell the story. What do you include? What do you leave out? What do you emphasize? How do you describe things? (And a thousand other details.)

There's an analogy with photography. A thousand people might snap a shot of something but it's the photographer that produces the memorable image. Why? They say it's because he or she has an eye. What they mean is that the photographer has an interesting way of looking at things and framing images.

A photographer's eye, an author's voice; it seems to me it's about how you express your unique perspective.

What do you think?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

[I wrote the following in March, 2009]

I've been thinking about voice as I've caught up on my Newbery reading. I was particularly struck by the voices in Niel Gaiman's The Graveyard Book and in Savvy by Ingrid Law.

Savvy is the kind of 1st person narrative that comes first to mind when we talk about voice. The 13-year-old narrator sounds like a unique individual from the beginning.

The Graveyard Book is 3rd person (with occasional narrative intrusions), but it has voice too. How so? I don't have specific examples, but it's easy to imagine that the story would have been much less charming if told differently.

The notion that voice = characters-with-attitude is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg (if it doesn't miss the point entirely). I think voice = storytelling.

Go back to the primordial camp fires. What has always set the storyteller apart from the rest? The way they tell the story. In the old days, every one knew the story but some could tell it better than others.

This gets to the heart of voice--your voice as an author: it's about how you tell the story. What do you include? What do you leave out? What do you emphasize? How do you describe things? (And a thousand other details.)

There's an analogy with photography. A thousand people might snap a shot of something but it's the photographer that produces the memorable image. Why? They say it's because he or she has an eye. What they mean is that the photographer has an interesting way of looking at things and framing images.

A photographer's eye, an author's voice; it seems to me it's about how you express your unique perspective.

What do you think?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Why Publish?

Writing Wednesday

This is a very good question; one everyone with any pretense of scribbling and getting paid for it should consider carefully. With the advent of the Internet, there are more ways to share one's writing with others than ever before. Publishing in the commercial market is a trying and exhausting undertaking, and yet I've met far more people aspiring to publication than the ones who think they should be professional musicians even though the requirements for success are similar.

Why do people believe they should be published?

If you should manage to finish a long-form writing project, it's very hard not to be sucked in by the "cute kid" syndrome: you can't believe that everyone else doesn't love your baby as much as you do.

So why do I want to publish my work?

I've thought long and hard about my own motivations. I've concluded that I want to write for the commercial market because I want economic permission to keep playing in the universe of my imagination--much like the intrepid explorer presenting the findings from one expedition to the geographical society to convince them to support subsequent expeditions.

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

This is a very good question; one everyone with any pretense of scribbling and getting paid for it should consider carefully. With the advent of the Internet, there are more ways to share one's writing with others than ever before. Publishing in the commercial market is a trying and exhausting undertaking, and yet I've met far more people aspiring to publication than the ones who think they should be professional musicians even though the requirements for success are similar.

Why do people believe they should be published?

- I heard one writer say that many people confuse their passion for reading with a desire to write.

- There's a related tendency to think that because you can write, you can write better than the trash churned out by the publishers.

- Many people who say they dream of being a writing really mean that they dream of having written and then basking in the glow of that accomplishment.

If you should manage to finish a long-form writing project, it's very hard not to be sucked in by the "cute kid" syndrome: you can't believe that everyone else doesn't love your baby as much as you do.

So why do I want to publish my work?

I've thought long and hard about my own motivations. I've concluded that I want to write for the commercial market because I want economic permission to keep playing in the universe of my imagination--much like the intrepid explorer presenting the findings from one expedition to the geographical society to convince them to support subsequent expeditions.

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

Check Lists

Technique Tuesday

A book called The Checklist Manifesto* has been getting a fair amount of attention recently. And rightly so: its message that complexity can be managed through the time-honored (if often only in the breach) pattern of a check list.

Here's what Steven D. Levitt at the Freakonomics blog had to say about the book:

But in the particular context of little systems, I wanted to lead off with an example with which people should have some familiarity. A check list, you see, is a canonical example of a little system. Like the mark etched on the coffee pots, check lists simplify a process by reducing it to a series of small steps or checks.

The magic is not in the list, but the steps. A list like:

It's not that little systems like check lists take away our responsibility to think, it's that they help us simplify what would otherwise be a complex situation.

What common activities can you simplify with a check list?

* I receive no benefit for the Amazon link. I've provided it simply as a courtesy.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

A book called The Checklist Manifesto* has been getting a fair amount of attention recently. And rightly so: its message that complexity can be managed through the time-honored (if often only in the breach) pattern of a check list.

Here's what Steven D. Levitt at the Freakonomics blog had to say about the book:

The book’s main point is simple: no matter how expert you may be, well-designed check lists can improve outcomes (even for Gawande’s own surgical team). The best-known use of checklists is by airplane pilots. Among the many interesting stories in the book is how this dedication to checklists arose among pilots.I have not read this book yet, but I wanted to mention it to show that I'm not the only one who thinks checklists are a good idea.

But in the particular context of little systems, I wanted to lead off with an example with which people should have some familiarity. A check list, you see, is a canonical example of a little system. Like the mark etched on the coffee pots, check lists simplify a process by reducing it to a series of small steps or checks.

The magic is not in the list, but the steps. A list like:

- Find site for evil lair

- Recruit minions

- Invent doomsday device

- Take over world

It's not that little systems like check lists take away our responsibility to think, it's that they help us simplify what would otherwise be a complex situation.

What common activities can you simplify with a check list?

* I receive no benefit for the Amazon link. I've provided it simply as a courtesy.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Monday, April 26, 2010

Systems

Making Monday

Systems and structures have been a fundamental part of the way I understand the world for as long as I can remember. If it's not the innate product of some gene, then the genesis of my systematic perspective probably dates back to the Lego™ set I had as a child.

I received both formal and informal training in systems at school: I was influenced by the book, Gödel, Escher, Bach, and I took a course called Systems Dynamics. After all of that, I can give you the following brief definition: a system is a set of symbols and the rules by which those symbols may be manipulated.

That may sound pretty abstract, but in simple, concrete terms, a system is a game. The symbols are the pieces or the players, and the rules are ... the rules.

If you stop and think about it, practically everything in the human world is a system: all our technology, our laws, our businesses, and most kinds of social interactions involve things that can be manipulated and rules for manipulating them.

Even things that appear to be single objects can be systems in both their structure and the sequence of operations by which they are produced.

A systematic perspective is at the core of the practical arts of the makers. Put another way, to be a maker, you must understand the relationships between the whole and the parts.

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Systems and structures have been a fundamental part of the way I understand the world for as long as I can remember. If it's not the innate product of some gene, then the genesis of my systematic perspective probably dates back to the Lego™ set I had as a child.

I received both formal and informal training in systems at school: I was influenced by the book, Gödel, Escher, Bach, and I took a course called Systems Dynamics. After all of that, I can give you the following brief definition: a system is a set of symbols and the rules by which those symbols may be manipulated.

That may sound pretty abstract, but in simple, concrete terms, a system is a game. The symbols are the pieces or the players, and the rules are ... the rules.

If you stop and think about it, practically everything in the human world is a system: all our technology, our laws, our businesses, and most kinds of social interactions involve things that can be manipulated and rules for manipulating them.

Even things that appear to be single objects can be systems in both their structure and the sequence of operations by which they are produced.

A systematic perspective is at the core of the practical arts of the makers. Put another way, to be a maker, you must understand the relationships between the whole and the parts.

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Friday, April 23, 2010

RSMSLWALF Forever

Free-form Friday

Politics has always been a dangerous game, but of late the sport as played in the US seems to have become increasingly divisive.

That said, I have some good news for young people who feel trapped in a teenage wasteland: some of the stuff you come up with may have lasting value.

Case in point: in high school, Anthony Ferro and I decided that our school government needed an infusion of nerd energy so we ran for student body president and VP. Since we thought more broadly than many of our class mates, the first order of business was to form an appropriate political party: RSMSLWALF (pronounced "rams-walf").

RSMSLWALF stands for the Right Side of the Middle of the Stream Left Wing Apathetics Liberation Front.

Given the pundit-fueled shouting matches parading by on the evening news that pass for political discourse, and how little I care for people who are more concerned with disagreeing than solving problems, perhaps it's time to liberate like-mined apathetics; perhaps it's time for RSMSLWALF!

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Politics has always been a dangerous game, but of late the sport as played in the US seems to have become increasingly divisive.

That said, I have some good news for young people who feel trapped in a teenage wasteland: some of the stuff you come up with may have lasting value.

Case in point: in high school, Anthony Ferro and I decided that our school government needed an infusion of nerd energy so we ran for student body president and VP. Since we thought more broadly than many of our class mates, the first order of business was to form an appropriate political party: RSMSLWALF (pronounced "rams-walf").

RSMSLWALF stands for the Right Side of the Middle of the Stream Left Wing Apathetics Liberation Front.

Given the pundit-fueled shouting matches parading by on the evening news that pass for political discourse, and how little I care for people who are more concerned with disagreeing than solving problems, perhaps it's time to liberate like-mined apathetics; perhaps it's time for RSMSLWALF!

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Thursday, April 22, 2010

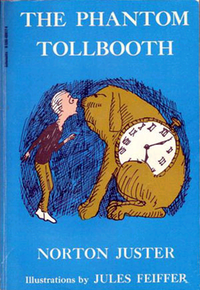

Influential Book: The Phantom Tollbooth

Reading thuRsday

For me, The Phantom Tollbooth, by Norton Juster was an early experience with a something surreal that said more to me than the real.

Even as a child, I knew that the story was about abstractions, but that didn't stop it from being a hyper-real experience. I was there with Milo as he conducted the chromatic orchestra and saw the vivid hues of the proper sunrise and well as the unreal colors when the orchestra got out of control. And even though I was on-board 100% with the closing message of finding the wonder in the world around us, the melancholy I felt when Milo left Rhyme and Reason and drove back past the toll booth was lightened by the hope that I might receive a toll booth in the mail one day.

Published in 1961, it might come off as a bit too didactic by current standards. But that doesn't stop the book from having a cherished place as a classic in my personal library.

While looking up the references, I came across a note that Warner Brothers is developing a remake of the Phantom Tollbooth. And a plea on the Normality Restored blog for Hollywood to leave this one alone. I say, "amen."

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

For me, The Phantom Tollbooth, by Norton Juster was an early experience with a something surreal that said more to me than the real.

Even as a child, I knew that the story was about abstractions, but that didn't stop it from being a hyper-real experience. I was there with Milo as he conducted the chromatic orchestra and saw the vivid hues of the proper sunrise and well as the unreal colors when the orchestra got out of control. And even though I was on-board 100% with the closing message of finding the wonder in the world around us, the melancholy I felt when Milo left Rhyme and Reason and drove back past the toll booth was lightened by the hope that I might receive a toll booth in the mail one day.

Published in 1961, it might come off as a bit too didactic by current standards. But that doesn't stop the book from having a cherished place as a classic in my personal library.

While looking up the references, I came across a note that Warner Brothers is developing a remake of the Phantom Tollbooth. And a plea on the Normality Restored blog for Hollywood to leave this one alone. I say, "amen."

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

Why Write Fiction?

Writing Wednesday

Why do I write fiction? Because sometimes the jester is the only one in the court who can speak the truth. And because sometimes the untrue is more true than the true.

One of the fundamental rules of writing is, "Show, don't tell." This is actually a fundamental rule for life; people are much more willing to adopt an idea if you show them how to arrive at the notion themselves than if you hand it to them finished, polished, and ready to place on their mantle. A story can be spun that shows how concepts affect the lives of one's characters much more clearly than trying to find an example in the life of an actual person.

One of the things I learned in graduate school is that there is no such thing as "objective" history; every attempt to recapture the past is an interpretation in which some things are emphasized more than others. We build models for the same reason: to emphasize some aspects of the thing being modeled while ignoring others. In other words, models are a simplification of reality. Fiction is the literary equivalent of model making.

What are your favorite examples of a work of fiction that expresses a truth better than reality?

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Why do I write fiction? Because sometimes the jester is the only one in the court who can speak the truth. And because sometimes the untrue is more true than the true.

One of the fundamental rules of writing is, "Show, don't tell." This is actually a fundamental rule for life; people are much more willing to adopt an idea if you show them how to arrive at the notion themselves than if you hand it to them finished, polished, and ready to place on their mantle. A story can be spun that shows how concepts affect the lives of one's characters much more clearly than trying to find an example in the life of an actual person.

One of the things I learned in graduate school is that there is no such thing as "objective" history; every attempt to recapture the past is an interpretation in which some things are emphasized more than others. We build models for the same reason: to emphasize some aspects of the thing being modeled while ignoring others. In other words, models are a simplification of reality. Fiction is the literary equivalent of model making.

What are your favorite examples of a work of fiction that expresses a truth better than reality?

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Little Systems

Technique Tuesday

Time and again, I'll learn of a new idea, particularly in software development, only to find that it's something I'm doing or already understand, though perhaps not in quite the terms or with quite the eloquence of the new explanation.

I had that experience years ago when I read Jim McCarthy's Dynamics of Software Development and came to his discussion of little systems.

Jim gave the example of a pair of coffee shops in Seattle (this was before all coffee shops were Starbucks shops--sometime in the late Cretaceous, I think). In one shop, the coffee was consistently excellent. In the other, it was hit-or-miss. The shops were the same in all material aspects: similar facilities, locations, offerings, staff, and clients. The only difference was that in the consistently good shop all the pots had been etched with a line about half-an-inch from the bottom and there was a standing rule that if the level fell below the line the staff was to brew a new pot.

That line made a significant difference because when things got busy in the hit-or-miss shop the staff wouldn't notice they were out until they drained a pot. Then customers had to wait until the staff brewed a new pot. If there were too many people in line, the temptation to pull the pot early would become irresistible.

In terms of software development, Jim pointed out that where big, complex development systems generally only succeed in preventing productivity, small systems can provide a big productivity boost.

The coffee pot system is about as simple as they come: one mark and one rule. If I hadn't labeled it as a "little system," you might likely have barely noticed it if you were being trained to work in that shop. The key point is that little systems blend into the background and become nothing more than "the way we do things here." If the system requires enough ceremony that you notice when you use the system, it's too big.

You probably already use a number of little systems. I, for example, make a point of paying when I receive a bill when I receive it (arguments about earning every micro-cent of interest by waiting till the last moment aside) because it gives me the mental space to focus on my writing without worrying that I've forgotten to honor an obligation.

What little systems have you developed? I'm particularly interested in the ones that help you when you're making.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Time and again, I'll learn of a new idea, particularly in software development, only to find that it's something I'm doing or already understand, though perhaps not in quite the terms or with quite the eloquence of the new explanation.

I had that experience years ago when I read Jim McCarthy's Dynamics of Software Development and came to his discussion of little systems.

Jim gave the example of a pair of coffee shops in Seattle (this was before all coffee shops were Starbucks shops--sometime in the late Cretaceous, I think). In one shop, the coffee was consistently excellent. In the other, it was hit-or-miss. The shops were the same in all material aspects: similar facilities, locations, offerings, staff, and clients. The only difference was that in the consistently good shop all the pots had been etched with a line about half-an-inch from the bottom and there was a standing rule that if the level fell below the line the staff was to brew a new pot.

That line made a significant difference because when things got busy in the hit-or-miss shop the staff wouldn't notice they were out until they drained a pot. Then customers had to wait until the staff brewed a new pot. If there were too many people in line, the temptation to pull the pot early would become irresistible.

In terms of software development, Jim pointed out that where big, complex development systems generally only succeed in preventing productivity, small systems can provide a big productivity boost.

The coffee pot system is about as simple as they come: one mark and one rule. If I hadn't labeled it as a "little system," you might likely have barely noticed it if you were being trained to work in that shop. The key point is that little systems blend into the background and become nothing more than "the way we do things here." If the system requires enough ceremony that you notice when you use the system, it's too big.

You probably already use a number of little systems. I, for example, make a point of paying when I receive a bill when I receive it (arguments about earning every micro-cent of interest by waiting till the last moment aside) because it gives me the mental space to focus on my writing without worrying that I've forgotten to honor an obligation.

What little systems have you developed? I'm particularly interested in the ones that help you when you're making.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Monday, April 19, 2010

Makers vs. Users

Making Monday

Sometimes, it's easier to define something in terms of what it is not. In the case of makers, they stand in opposition to users.

Where makers believe that, at some level, a thing has intrinsic worth and thus a right to exist apart from all other things, users believe that things have a right to exist only as a means to an end.

What does that mean?

Here's a simple example: many of the settlers of European descent coming into the western part of North America declared vast portions to be "wastelands" because they couldn't be used for agriculture.

Now, to be clear, in an absolute sense we are all users. At meal time, we generally don't concern ourselves about the rights of the animals and vegetables we consume to exist independently because they have become a means to the end of our own existence.

The difference I'm trying to get at is, at one level, a relative one, but at another it's deeply significant: for the users, nothing is sacred. The contrast is illustrated in the (perhaps apocryphal) story that the Indian hunter would apologize for killing the deer, thanking it for what he needed to feed his family while the buffalo hunters simply slaughtered the animals because they were a nuisance.

Users see the value in a thing as long as it serves their purposes.

Makers, like parents bringing a child into the world, look forward to the day when the thing they created takes on a life of its own.

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Sometimes, it's easier to define something in terms of what it is not. In the case of makers, they stand in opposition to users.

Where makers believe that, at some level, a thing has intrinsic worth and thus a right to exist apart from all other things, users believe that things have a right to exist only as a means to an end.

What does that mean?

Here's a simple example: many of the settlers of European descent coming into the western part of North America declared vast portions to be "wastelands" because they couldn't be used for agriculture.

Now, to be clear, in an absolute sense we are all users. At meal time, we generally don't concern ourselves about the rights of the animals and vegetables we consume to exist independently because they have become a means to the end of our own existence.

The difference I'm trying to get at is, at one level, a relative one, but at another it's deeply significant: for the users, nothing is sacred. The contrast is illustrated in the (perhaps apocryphal) story that the Indian hunter would apologize for killing the deer, thanking it for what he needed to feed his family while the buffalo hunters simply slaughtered the animals because they were a nuisance.

Users see the value in a thing as long as it serves their purposes.

Makers, like parents bringing a child into the world, look forward to the day when the thing they created takes on a life of its own.

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Saturday, April 17, 2010

What is Young Adult as a Genre?

I felt compelled to comment about the genre of young adult literature after listening to the March 14th Writing Excuses Podcast,* not because I take exception but because I think I have a crisper definition of "young adult."

Under the title of "Writing for Young Adults," they touched on the conventions that define the genre in terms of age (young adult = teenagers) and subject matter (high school with its social dynamics, particularly first loves). To their credit, they tried to get beyond those conventions. They talked around several important ideas but didn't land on what I think is the key distinction: young adult is essentially about the transition between childhood and adulthood.

Of course, not every story involving a teenager is about the transition. In fact, there are lots of stories about teenagers who never really change. Those stories are "young adult" only in the loose sense that their protagonists and most of their characters fall into the right age range.

But in a broader sense, because the transition between childhood and adulthood is such a fundamental part of those years, it's difficult to tell stories involving young people without at least touching upon the fact that they are in the middle of becoming something other than what they were.

Besides the rich opportunities for conflict (and the clichés of angst-ridden, perpetually depressed teenagers), one of the reasons I enjoy spinning stories in and about the great transition is that it is a time of life that is essentially hopeful: change is unavoidable and carries the prospect of becoming something better and more wonderful than you ever imagined. Adults, on the other hand, have largely shaped themselves into that they will be: change is much more difficult and hence much rarer.

Because of the hopeful possibilities implicit in the transition between childhood and adulthood, I've focus my efforts on producing thoughtful books for people navigating the Great Between.

* A transcript of the podcast is available at the A Word in Your Eye blog.

Image: Carlos Porto / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Under the title of "Writing for Young Adults," they touched on the conventions that define the genre in terms of age (young adult = teenagers) and subject matter (high school with its social dynamics, particularly first loves). To their credit, they tried to get beyond those conventions. They talked around several important ideas but didn't land on what I think is the key distinction: young adult is essentially about the transition between childhood and adulthood.

Of course, not every story involving a teenager is about the transition. In fact, there are lots of stories about teenagers who never really change. Those stories are "young adult" only in the loose sense that their protagonists and most of their characters fall into the right age range.

But in a broader sense, because the transition between childhood and adulthood is such a fundamental part of those years, it's difficult to tell stories involving young people without at least touching upon the fact that they are in the middle of becoming something other than what they were.

Besides the rich opportunities for conflict (and the clichés of angst-ridden, perpetually depressed teenagers), one of the reasons I enjoy spinning stories in and about the great transition is that it is a time of life that is essentially hopeful: change is unavoidable and carries the prospect of becoming something better and more wonderful than you ever imagined. Adults, on the other hand, have largely shaped themselves into that they will be: change is much more difficult and hence much rarer.

Because of the hopeful possibilities implicit in the transition between childhood and adulthood, I've focus my efforts on producing thoughtful books for people navigating the Great Between.

* A transcript of the podcast is available at the A Word in Your Eye blog.

Image: Carlos Porto / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Friday, April 16, 2010

Future FAQ: Which of your books is your favorite?

Free-form Friday

Today's theme doesn't guarantee humor. Free-form Friday is analogous to the "Potpourri" category on the game show Jeopardy. In that vein, I offer an entry in my future FAQ.* While it may seem dangerously close to counting one's chickens before they hatch, here is my answer to one of the questions I anticipate after I've published a number of books.

Which of your books is your favorite?

If you tell me which of your children is your favorite, I'll tell you which of my books is my favorite.

"Wait," you say, "that's not fair!"

My point exactly.

If you're still not going to let me off the hook, may I say, "All of them?"

No? I can only name one? Then I'll say, "The one I'm currently writing."

*FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Today's theme doesn't guarantee humor. Free-form Friday is analogous to the "Potpourri" category on the game show Jeopardy. In that vein, I offer an entry in my future FAQ.* While it may seem dangerously close to counting one's chickens before they hatch, here is my answer to one of the questions I anticipate after I've published a number of books.

Which of your books is your favorite?

If you tell me which of your children is your favorite, I'll tell you which of my books is my favorite.

"Wait," you say, "that's not fair!"

My point exactly.

If you're still not going to let me off the hook, may I say, "All of them?"

No? I can only name one? Then I'll say, "The one I'm currently writing."

*FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Thursday, April 15, 2010

Influential Book: The Chronicles of Prydain and Taran Wanderer

Reading thuRsday

One of the series I read after The Chronicles of Narnia and Lord of the Rings was Lloyd Alexander's The Chronicles of Prydain.

I owe my sense of Wales as a magical place almost entirely to Mr. Alexander's books.

When I read the entire series to my son several years ago, I saw with my adult eyes that they are perhaps not the pinnacle of literary expression but they still spoke to me. They spoke to me in a powerful way when I read them for the first time as a young person. I was captivated by Taran's journey from assistant pig-keeper to King of Prydain. I think the theme of growing and becoming resonated strongly with me as I undertook my own journey through the great between we call the teenage years.

Perhaps that's why the fourth volume, Taran' Wanderer is my favorite. The story of Taran's attempts to find his place in the world through a series of apprenticeships directly addressed my own hopes and fears. As I followed along with Taran, it was almost as if I were reading a guide to maturation and an introduction to manly virtues.

I think this is more a commentary on me and what I brought to the books than on the books themselves. But isn't that what makes a work influential: what you bring to and take away from the experience of the work?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

One of the series I read after The Chronicles of Narnia and Lord of the Rings was Lloyd Alexander's The Chronicles of Prydain.

I owe my sense of Wales as a magical place almost entirely to Mr. Alexander's books.

When I read the entire series to my son several years ago, I saw with my adult eyes that they are perhaps not the pinnacle of literary expression but they still spoke to me. They spoke to me in a powerful way when I read them for the first time as a young person. I was captivated by Taran's journey from assistant pig-keeper to King of Prydain. I think the theme of growing and becoming resonated strongly with me as I undertook my own journey through the great between we call the teenage years.

Perhaps that's why the fourth volume, Taran' Wanderer is my favorite. The story of Taran's attempts to find his place in the world through a series of apprenticeships directly addressed my own hopes and fears. As I followed along with Taran, it was almost as if I were reading a guide to maturation and an introduction to manly virtues.

I think this is more a commentary on me and what I brought to the books than on the books themselves. But isn't that what makes a work influential: what you bring to and take away from the experience of the work?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

Why Write Books?

Writing Wednesday

Of those who suffer from the pretense (or compulsion) to scribble, some undertake to produce the kind of longer works we call books. If it is a bit presumptuous to think that someone else will want to read a blog entry or article, it must be the height of presumption to think that someone else will want to spend eight to ten hours reading your words.

But you can weave a sort of magic with long-form works; you can conjure a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts. Think of a symphony where a motif reappears, juxtaposed with a different theme and suddenly it speaks to you in a whole new way. Or consider the way two people who who have known each other a long time and speak volumes with a word, a gesture, of even a glance.

You see, at a fundamental level, context creates meaning. Why are your children more significant to you than other children? You know their context, sometimes even better than they do.

Long-form works can provide more context, which can make their key moments more meaningful. Notice the conditionals? The long form doesn't guarantee greater significance, it only makes it possible.

One of the fundamental ideas I want to consider and share in my writing is the basic notion of getting beyond one's self. One of the first ways to do so is to become aware of your context. While there are short stories about enlightenment (most religions traditions have a number of such stories), a full exploration practically demands the longer form.

Put another way, learning is much like a journey. You can learn a few things from a short trip. You can learn many things from a longer excursion. The difference comes from the number of opportunities for learning you can embrace in a given amount of time.

I have a lot that I would like to share--stories to tell and ideas to consider--and so I invite you to join me for the journey. I hope to delight you with the long-form as characters and events weave together into a whole that says more than any one of the parts.

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Of those who suffer from the pretense (or compulsion) to scribble, some undertake to produce the kind of longer works we call books. If it is a bit presumptuous to think that someone else will want to read a blog entry or article, it must be the height of presumption to think that someone else will want to spend eight to ten hours reading your words.

But you can weave a sort of magic with long-form works; you can conjure a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts. Think of a symphony where a motif reappears, juxtaposed with a different theme and suddenly it speaks to you in a whole new way. Or consider the way two people who who have known each other a long time and speak volumes with a word, a gesture, of even a glance.

You see, at a fundamental level, context creates meaning. Why are your children more significant to you than other children? You know their context, sometimes even better than they do.

Long-form works can provide more context, which can make their key moments more meaningful. Notice the conditionals? The long form doesn't guarantee greater significance, it only makes it possible.

One of the fundamental ideas I want to consider and share in my writing is the basic notion of getting beyond one's self. One of the first ways to do so is to become aware of your context. While there are short stories about enlightenment (most religions traditions have a number of such stories), a full exploration practically demands the longer form.

Put another way, learning is much like a journey. You can learn a few things from a short trip. You can learn many things from a longer excursion. The difference comes from the number of opportunities for learning you can embrace in a given amount of time.

I have a lot that I would like to share--stories to tell and ideas to consider--and so I invite you to join me for the journey. I hope to delight you with the long-form as characters and events weave together into a whole that says more than any one of the parts.

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

Dear-Editor.com's Giveaway - a Free YA/MG Edit

I wanted* to let you know that Dear-Editor.com is giving away a free substantive edit for a completed MG/YA manuscript of not more than 85,000 words. The deadline is MIDNIGHT, APRIL 14, 2010, PST. (Here's the perma-link to the contest page.)

What is a substantive edit?

So, if you have a qualifying manuscript, run, don't walk, to enter.

*In truth, I would like to get the substantive edit for my manuscript and spreading the word like earns me another entry. As a matter of fact, I'd prefer none of you enter so as to improve my chances. So much for my veneer of nobility.

What is a substantive edit?

In a “Substantive Edit,” the author receives general feedback about the manuscript’s overall pacing, organization, narrative voice, plot development/narrative arc, characterization, point of view, setting, delivery of background information, adult sensibility (children’s books only), and the synchronicity of age-appropriate subject matter with target audience, as the Editor determines appropriate and necessary after reviewing the entire manuscript. It is not a word-by-word, line-by-line “Line Edit.” - Deborah Halverson, the Dear Editor editor

So, if you have a qualifying manuscript, run, don't walk, to enter.

*In truth, I would like to get the substantive edit for my manuscript and spreading the word like earns me another entry. As a matter of fact, I'd prefer none of you enter so as to improve my chances. So much for my veneer of nobility.

Writing Technology: Netbooks

Technique Tuesday

I acquired my first laptop in 1998. It was a state-of-the-art Pentium II with 64 MB of memory and a 4 GB hard drive. Most phones now have more computing power than that.

I mention this old system because as the years passed, I took increasing pride in keeping it running and doing useful work for me. Once it could no longer run the current Windows operating system, I found a small version of Linux and had a perfectly capable system that could browse the internet and support the usual reading and writing tasks. Of course as newer laptops became lighter and more powerful it became more challenging to find tasks that weren't too much trouble to do on the old laptop.

I thought I'd found a perfect use for the old system as the mobile text editor on which to draft my book. The Linux distribution gave me a character-mode editor, the system was old enough that it was easy to turn off all internet-related distractions, and as a laptop, I could take it to a quiet part of the house where I wouldn't be distracted by the work-related materials that littered my desk.

The arrangement ended when the laptop's screen died. The tragedy was that the system worked just fine with an external monitor. But since mobility was a big part of the value the system provided me, I reluctantly decided that it was time to upgrade.

Because I have other computers, I chose a netbook: specifically, an Acer Aspire One AOD250*. I've provided a link and the image to give you a point of references, and not to recommend this particular system above other netbooks.

Some people call netbooks underpowered laptops and claim that they can barely keep up with modern applications. That may well be. I did remove a fair amount of shovel-ware**. But because I use the system as a text editor, it's been more than powerful enough for my needs.

That's what I expected. What I didn't expect is how useful the fact that it's small, light, and will run for eight to nine hours before the battery needs to be charged would be. Put another way, I've found myself using the netbook far more than I anticipated.

So, if you're looking for a writing platform, you may want to think seriously about a netbook.

* I have no connection with Acer and received no consideration for this mention.

** Shovel-ware: software of variable value included with a system by the manufacturer.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

I acquired my first laptop in 1998. It was a state-of-the-art Pentium II with 64 MB of memory and a 4 GB hard drive. Most phones now have more computing power than that.

I mention this old system because as the years passed, I took increasing pride in keeping it running and doing useful work for me. Once it could no longer run the current Windows operating system, I found a small version of Linux and had a perfectly capable system that could browse the internet and support the usual reading and writing tasks. Of course as newer laptops became lighter and more powerful it became more challenging to find tasks that weren't too much trouble to do on the old laptop.

I thought I'd found a perfect use for the old system as the mobile text editor on which to draft my book. The Linux distribution gave me a character-mode editor, the system was old enough that it was easy to turn off all internet-related distractions, and as a laptop, I could take it to a quiet part of the house where I wouldn't be distracted by the work-related materials that littered my desk.

The arrangement ended when the laptop's screen died. The tragedy was that the system worked just fine with an external monitor. But since mobility was a big part of the value the system provided me, I reluctantly decided that it was time to upgrade.

Because I have other computers, I chose a netbook: specifically, an Acer Aspire One AOD250*. I've provided a link and the image to give you a point of references, and not to recommend this particular system above other netbooks.

Some people call netbooks underpowered laptops and claim that they can barely keep up with modern applications. That may well be. I did remove a fair amount of shovel-ware**. But because I use the system as a text editor, it's been more than powerful enough for my needs.

That's what I expected. What I didn't expect is how useful the fact that it's small, light, and will run for eight to nine hours before the battery needs to be charged would be. Put another way, I've found myself using the netbook far more than I anticipated.

So, if you're looking for a writing platform, you may want to think seriously about a netbook.

* I have no connection with Acer and received no consideration for this mention.

** Shovel-ware: software of variable value included with a system by the manufacturer.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Monday, April 12, 2010

Makers and Integrity

Making Monday

In the charter statement for this blog, I wrote:

Integrity? Means? Ends?

Let's be clear on these ideas.

Integrity

Many people think integrity means being honest. Good sailors and science fiction fans know the term, "hull integrity." While a sailor might say that, "She's an honest ship, good and true," they're not really talking about the moral character of the boat. They're referring to the soundness of the design and construction.

Integrity really means wholeness or completeness. So, a person who is morally complete would be honest, but that's only a facet of their integrity.

Ends

The object or goal of one's efforts. The purpose for which something in undertaken. What you're trying to do.

Means

The methods by which one can pursue or achieve their ends. How you're trying to do it.

Ethical Issues

It's probably clear that not all possible goals are good. That's why, for example, it's hard to believe the over-the-top villain who wants to destroy his own world (and presumably himself in the process).

Many people, however, get hung up on the problem that even when we have an end we all agree is good, not all means of achieving that end are good. Hence the aphorism that the ends don't justify the means.

Utilitarianism presents a related but more subtle trap: attributing no worth to a thing that doesn't serve a purpose.

Makers, of course, are keenly aware of utility: if a thing doesn't function as intended its making isn't finished. But makers also comprehend the beauty of a thing in itself, apart from any particular utility. That is how they come to know and understand its integrity.

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

In the charter statement for this blog, I wrote:

In order to focus on the quality and integrity of a thing it needs to have some intrinsic worth. In philosophic terms, it must, in some sense, be an end in and of itself. Quality becomes accidental, or at best conditional, when the thing is merely an means to some other end.

Integrity? Means? Ends?

Let's be clear on these ideas.

Integrity

Many people think integrity means being honest. Good sailors and science fiction fans know the term, "hull integrity." While a sailor might say that, "She's an honest ship, good and true," they're not really talking about the moral character of the boat. They're referring to the soundness of the design and construction.

Integrity really means wholeness or completeness. So, a person who is morally complete would be honest, but that's only a facet of their integrity.

Ends

The object or goal of one's efforts. The purpose for which something in undertaken. What you're trying to do.

Means

The methods by which one can pursue or achieve their ends. How you're trying to do it.

Ethical Issues

It's probably clear that not all possible goals are good. That's why, for example, it's hard to believe the over-the-top villain who wants to destroy his own world (and presumably himself in the process).

Many people, however, get hung up on the problem that even when we have an end we all agree is good, not all means of achieving that end are good. Hence the aphorism that the ends don't justify the means.

Utilitarianism presents a related but more subtle trap: attributing no worth to a thing that doesn't serve a purpose.

Makers, of course, are keenly aware of utility: if a thing doesn't function as intended its making isn't finished. But makers also comprehend the beauty of a thing in itself, apart from any particular utility. That is how they come to know and understand its integrity.

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Friday, April 9, 2010

A Flotilla of Flummoxing Flamingos

Free-form Friday

I should probably begin by explaining the flotilla of flummoxing flamingos.

Here's the offending line:

It all came about because my friend, Pat Martinez, invited us to play with the present participle in adjective form.

It was a fun little exercise, but fun can lead to trouble: now I need to know who Penderwick is and why he seems to be afflicted with flamingos.

Image: Darren Robertson / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

I should probably begin by explaining the flotilla of flummoxing flamingos.

Here's the offending line:

The next morning, Penderwick's front walk was blocked, again, by a flotilla of flummoxing flamingos.

It all came about because my friend, Pat Martinez, invited us to play with the present participle in adjective form.

"We can take a plain old verb and change it to a present participle by simply adding ing. We can then use it to modify a noun. Notice the fun language and description that comes to life."

It was a fun little exercise, but fun can lead to trouble: now I need to know who Penderwick is and why he seems to be afflicted with flamingos.

Image: Darren Robertson / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Thursday, April 8, 2010

First Fantasy

Reading thuRsday

The first fantasy book that captured and catalyzed my imagination was the last book in the Chronicles of Narnia. I stumble upon The Last Battle in my elementary school library after exhausting their meager collection of books on World War II. I think it was the "battle" in the title that originally caught my eye.

I was mesmerized by the apocalyptic themes (it was easy to entertain apocalyptic notions during a time when everyone assumed nuclear war was inevitable) and enthralled by the conceptual scope of the fantasy. I found the theme of ever expanding vistas of worlds wider and richer than the one we know to be particularly compelling.

The transcendental surrealism (not a label I had at the time) of the story was far more effective than a mind-expanding drug. I got my first taste of the way in which one could understand something more deeply and vibrantly if they were unencumbered by the constraints of ordinary experience.

And that was it: one (metaphorical) puff and I was hooked.

What was the first fantasy novel you read?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

The first fantasy book that captured and catalyzed my imagination was the last book in the Chronicles of Narnia. I stumble upon The Last Battle in my elementary school library after exhausting their meager collection of books on World War II. I think it was the "battle" in the title that originally caught my eye.

I was mesmerized by the apocalyptic themes (it was easy to entertain apocalyptic notions during a time when everyone assumed nuclear war was inevitable) and enthralled by the conceptual scope of the fantasy. I found the theme of ever expanding vistas of worlds wider and richer than the one we know to be particularly compelling.

The transcendental surrealism (not a label I had at the time) of the story was far more effective than a mind-expanding drug. I got my first taste of the way in which one could understand something more deeply and vibrantly if they were unencumbered by the constraints of ordinary experience.

And that was it: one (metaphorical) puff and I was hooked.

What was the first fantasy novel you read?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

Why do you Write?

Writing Wednesday

Why do I write? The simplest answer is that, like everyone else, I need to express myself. And of the many modes of self-expression, I prefer those that are more permanent (than, say, a dance) when I need to "sound my barbaric YAWP over the roofs of the world."*

Indeed, if we define writing as assembling sequences of symbols in some medium--signatures, lists, notes, messages, letters, email, presentations, reports, and so on--almost everyone writes. Like ants who live in an exquisitely complex world of chemical signals, we live in a constant stream of encoded symbols.

But very few of us call ourselves writers. That's because "writers" produce a particular kind of writing: work that is consumed by people in general instead of someone in particular.

There is a question everyone who has ever flirted with the fantasy of writing for general consumption must answer for themselves: "Why do you think you can and should write things that others will want to read?"

There are many answers, but after you peel away motives like vanity and fame that can't endure the grueling course that is the life of writing, the only sustainable answer is that you write because you must.

I write because that's the only way to appease, at least for a time, the voices in my head.

Why do you write?

* Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, Stanza 52

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Why do I write? The simplest answer is that, like everyone else, I need to express myself. And of the many modes of self-expression, I prefer those that are more permanent (than, say, a dance) when I need to "sound my barbaric YAWP over the roofs of the world."*

Indeed, if we define writing as assembling sequences of symbols in some medium--signatures, lists, notes, messages, letters, email, presentations, reports, and so on--almost everyone writes. Like ants who live in an exquisitely complex world of chemical signals, we live in a constant stream of encoded symbols.

But very few of us call ourselves writers. That's because "writers" produce a particular kind of writing: work that is consumed by people in general instead of someone in particular.

There is a question everyone who has ever flirted with the fantasy of writing for general consumption must answer for themselves: "Why do you think you can and should write things that others will want to read?"

There are many answers, but after you peel away motives like vanity and fame that can't endure the grueling course that is the life of writing, the only sustainable answer is that you write because you must.

I write because that's the only way to appease, at least for a time, the voices in my head.

Why do you write?

* Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, Stanza 52

Image: Simon Howden / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

Writing Technology: Green Screens

Technique Tuesday

Let me begin by confessing that I'm still trying to work out what topics are appropriate for this theme. So, in the interim, I'm going to dive right into some technology. (Yes, it's the blogging equivalent of the magician waving a handkerchief to distract you while the assistant wheels the elephant onto the stage.)

I started playing with computers when green screen, character-mode displays were state-of-the art (I preferred amber over green, but that's another story). The original Macintosh (yes, that's what they were before they became hip enough to afford a three-letter name), splashed onto the scene with a full-time graphical user interface (GUI).

A few years later, folks from the English department at the University of Delaware published a study in which they argued that the quality of freshman papers written on a Macintosh was lower than those written on PC-class computers with character-mode displays. Oh, the papers produced on Macs looked better with well-laid-out text and proportional fonts, but (so the authors of the study claimed) the content of those papers was less well-thought-out than the papers composed without the graphical blandishments.* They suggested that this was because the students tended to believe that their papers were good (and more importantly finished) because they looked good.

The study and its claims were controversial. But I think there was a kernel of truth in the observation that there's value in a writing system that gets out of the way between you and your words; that removes even the little distractions life formatting.

Of course, now that we all use graphical interfaces the point may seem moot or at best hopelessly retro. Perhaps, but there are several applications for various platforms that give you a full screen with nothing there but your words.

I used a package called Write Monkey** on my Windows systems to finish drafting my current manuscript after I fell under the oppression of gainful employment and had substantially less time to write.

Having an editor in which I could focus entirely on my words helped me use my limited writing time well. You can achieve a similar effect with the Full Screen mode in your standard word processor. Perhaps it was the retro angle, but I enjoyed the way, Matrix-like, that the black background faded away and the words seemed to float free.

Of course, life is ever as simple as it should be and Write Monkey has its drawbacks, most of which come back to the fact that it is a text editor, not a word processor. This means that you get plain double quotes instead of the nice opening and closing quotes that Word supplies as you type. Also, Write Monkey doesn't convert a pair of dashes into an em-dash (again, like Word). I turned this liability into a feature: after writing about a chapter with Write Monkey, I import the text into Word and use the fact that quotes and em-dashes need to be corrected as an excuse to edit the new material.

For those of you who prefer Macs, I understand that Writeroom provides similar functionality. There's also JDarkRoom, which is written in Java and should run on your platform of choice.

What tools have you found that help you concentrate on your writing?

* Graphical Blandishments - that's how the animators for the Charlie Brown specials were credited.

** I have no connection with Write Monkey and received no consideration for this mention.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Let me begin by confessing that I'm still trying to work out what topics are appropriate for this theme. So, in the interim, I'm going to dive right into some technology. (Yes, it's the blogging equivalent of the magician waving a handkerchief to distract you while the assistant wheels the elephant onto the stage.)

I started playing with computers when green screen, character-mode displays were state-of-the art (I preferred amber over green, but that's another story). The original Macintosh (yes, that's what they were before they became hip enough to afford a three-letter name), splashed onto the scene with a full-time graphical user interface (GUI).

A few years later, folks from the English department at the University of Delaware published a study in which they argued that the quality of freshman papers written on a Macintosh was lower than those written on PC-class computers with character-mode displays. Oh, the papers produced on Macs looked better with well-laid-out text and proportional fonts, but (so the authors of the study claimed) the content of those papers was less well-thought-out than the papers composed without the graphical blandishments.* They suggested that this was because the students tended to believe that their papers were good (and more importantly finished) because they looked good.

The study and its claims were controversial. But I think there was a kernel of truth in the observation that there's value in a writing system that gets out of the way between you and your words; that removes even the little distractions life formatting.

Of course, now that we all use graphical interfaces the point may seem moot or at best hopelessly retro. Perhaps, but there are several applications for various platforms that give you a full screen with nothing there but your words.

I used a package called Write Monkey** on my Windows systems to finish drafting my current manuscript after I fell under the oppression of gainful employment and had substantially less time to write.

Having an editor in which I could focus entirely on my words helped me use my limited writing time well. You can achieve a similar effect with the Full Screen mode in your standard word processor. Perhaps it was the retro angle, but I enjoyed the way, Matrix-like, that the black background faded away and the words seemed to float free.

Of course, life is ever as simple as it should be and Write Monkey has its drawbacks, most of which come back to the fact that it is a text editor, not a word processor. This means that you get plain double quotes instead of the nice opening and closing quotes that Word supplies as you type. Also, Write Monkey doesn't convert a pair of dashes into an em-dash (again, like Word). I turned this liability into a feature: after writing about a chapter with Write Monkey, I import the text into Word and use the fact that quotes and em-dashes need to be corrected as an excuse to edit the new material.

For those of you who prefer Macs, I understand that Writeroom provides similar functionality. There's also JDarkRoom, which is written in Java and should run on your platform of choice.

What tools have you found that help you concentrate on your writing?

* Graphical Blandishments - that's how the animators for the Charlie Brown specials were credited.

** I have no connection with Write Monkey and received no consideration for this mention.

Image: luigi diamanti / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Monday, April 5, 2010

What is a Maker?

Making Monday

The simple (and simplistic answer) is someone who makes. Of course, the problem with a simple answer is that it doesn't work as often as it works.

What do I mean?

Consider the analogous question, "What is a writer?"* If we answer in an equally simplistic fashion, that a writer is someone who writes, then we've included everyone who arranges letters into words, from a thug scrawling graffiti to the author of a thousand page tome, in the definition. Implicit in the question is the qualifying assumption that others must find some value in your work to be a writer.

So, to play with the analogy, a maker would be someone whose work others value. That definition, at least, allows us to exclude, for example, people who make messes.

Oh, you might say, you mean creative types: artists, musicians, designers, etc.

Yes, but I also mean engineers. You see the making I'm getting at involves both hemispheres of the brain: on their own, right-brain passion and left-brain pragmatism produce works devoid of life. Both must be involved to bring a new thing into the universe.

Put another way, bright ideas (generally valued at a dime a dozen) are only the genesis of making. A true maker has both the skill and the fortitude to do the work (sometimes hard, sometimes tedious) to realize the idea and bring it to its final form.

To illustrate with writers, many people have ideas that could be great stories or books. What sets the writer apart from the many people is that they do the work to turn a, "Wouldn't it be cool if ...," into three or four hundred pages of coherent, entertaining prose.

Does that make sense? What do you think?

* We're speaking colloquially here. It would be more accurate to ask, "What set of activities and attributes are necessary and sufficient to call someone a writer?"

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

The simple (and simplistic answer) is someone who makes. Of course, the problem with a simple answer is that it doesn't work as often as it works.

What do I mean?

Consider the analogous question, "What is a writer?"* If we answer in an equally simplistic fashion, that a writer is someone who writes, then we've included everyone who arranges letters into words, from a thug scrawling graffiti to the author of a thousand page tome, in the definition. Implicit in the question is the qualifying assumption that others must find some value in your work to be a writer.

So, to play with the analogy, a maker would be someone whose work others value. That definition, at least, allows us to exclude, for example, people who make messes.

Oh, you might say, you mean creative types: artists, musicians, designers, etc.

Yes, but I also mean engineers. You see the making I'm getting at involves both hemispheres of the brain: on their own, right-brain passion and left-brain pragmatism produce works devoid of life. Both must be involved to bring a new thing into the universe.

Put another way, bright ideas (generally valued at a dime a dozen) are only the genesis of making. A true maker has both the skill and the fortitude to do the work (sometimes hard, sometimes tedious) to realize the idea and bring it to its final form.

To illustrate with writers, many people have ideas that could be great stories or books. What sets the writer apart from the many people is that they do the work to turn a, "Wouldn't it be cool if ...," into three or four hundred pages of coherent, entertaining prose.

Does that make sense? What do you think?

* We're speaking colloquially here. It would be more accurate to ask, "What set of activities and attributes are necessary and sufficient to call someone a writer?"

Image: Bill Longshaw / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Friday, April 2, 2010

Free-form Friday

In the world of work, Friday is often acknowledged as the end of the week with a relaxation of formality (e.g., casual or dress-down Friday). In the interests of not breaking too many traditions, my theme for Friday will be free-form. I'll lean toward fun and try not to stray into frivolous, although I shouldn't be too surprise if a flotilla of flummoxing flamingos made the occasional appearance.

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Image: Photography by BJWOK / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Thursday, April 1, 2010

Reading Thursday

For reasons that will become clearer with time, makers are more open to the worlds, both internal and external, and the wonders therein.

Similarly, the best writers are often also the best readers; literary omnivores.

On Thursdays, we'll look at books--primarily middle grade and young adult fiction, but we won't necessarily limit ourselves to those categories. We'll strive to improve our craft by appreciating good (and occasionally not-so-good) examples of others' work.

What recent books would you like to talk about?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Similarly, the best writers are often also the best readers; literary omnivores.

On Thursdays, we'll look at books--primarily middle grade and young adult fiction, but we won't necessarily limit ourselves to those categories. We'll strive to improve our craft by appreciating good (and occasionally not-so-good) examples of others' work.

What recent books would you like to talk about?

Image: Michelle Meiklejohn / FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)